The post How to Be a Food Policy Advocate in Your Community appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>Food policy experts Sarah Hackney and Jamie Fanous have advice for those who feel overwhelmed or unsure about how to make a difference. Hackney is the coalition director at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC) in Washington, D.C., where she works with grassroots organizations to advocate for federal policy reform to advance the sustainability of agriculture, food systems, natural resources and rural communities. Fanous is the policy director at one of these organizations, a California-based nonprofit called Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF). Together, Hackney and Fanous offer guidance on simple steps that we can all take to create positive change around us, in ways both big and small.

Join CSA programs and support food cooperatives

Besides doing the research to elect officials who advocate on behalf of these priorities, the best thing we can do to support farmers year-round is to be just as conscientious about how we vote with our dollars. “Sign up for a CSA, go to the farmers market or co-op, purchase your produce from farmers directly. Go the extra mile to do that,” says Fanous. “If you’re going to a big box store, the produce is probably not from a small-scale farmer or a local farmer, so it’s really not supporting local economies. Joining a CSA program is a great way to build a relationship with your farmer and know where your food is coming from.”

Educate yourself and amplify your actions

For those looking to engage more deeply in food policy advocacy, Hackney and Fanous recommend tuning into social media platforms and newsletters from a mixture of national agricultural organizations, such as NSAC, and local ones, such as CAFF.

“NSAC is one of the best places to get into the nerdy details of food and agriculture policy,” says Hackney. “We have a very active blog and a weekly e-newsletter where we highlight big food and ag policy news from D.C., along with free analysis you won’t find anywhere else.”

When it comes to understanding issues closer to home, Hackney says, “There are over 150 member organizations within NSAC, most of whom are state or regionally focused, and all of whom work in relationship with farmers and eaters in their communities. Almost all of them have active websites and social media accounts and some specifically have farmer- and consumer-led volunteer teams that help review and develop policy ideas both at the local and national level.” She recommends checking out the membership lists of a coalition such as NSAC or one of its peers, such as the HEAL Food Alliance, to see if there’s an active member organization in your state or region.

Call Congress

Once you start following political and agricultural news, you may come across the occasional public request for citizens like yourself to contact local representatives in Congress to advocate for or against certain bills.

“We share calls to action at key junctures in the policy process when there are opportunities for folks to make their voices heard directly with lawmakers,” says Hackney. “It’s absolutely possible for individual calls, emails and messages to make a difference: Lawmakers track and monitor who’s reaching out to them on issues that matter locally. When it comes to shifting food and farm policy toward more sustainable, equitable outcomes in our communities, we need those voices. We’re up against entrenched, well-resourced corporate interests and lobbying firms, and one of our best tools to push back is our willingness to speak up as voters, eaters and community leaders.”

“If organizations like CAFF or others ask—make the phone call. It makes a big difference,” says Fanous. “We very rarely ask people to make calls to their members, but when we do, it’s serious and we need that support. If you can’t make the call, repost the request on social media to give it more life.”

Vote every chance you get

Besides the four-year presidential election cycle, there are congressional elections every two years, as well as annual state and local elections. Register with Vote.org to receive notifications about upcoming elections so that you never miss a chance to vote.

“The coming 2024 election cycle may shape the fate and contents of the still-to-be-reauthorized farm bill,” says Hackney. The so-called “farm bill” should be passed by Congress every five years and pertains to much more than just farming. This package of legislation defines our food system, determining what we eat by how we use land, water and other natural resources.

“Congress didn’t reauthorize the 2018 Farm Bill on time last year, instead opting to extend the old bill,” explains Hackney. “If Congress doesn’t complete the reauthorization process on the bill before the fall, that could shift farm bill passage timing into 2025, which means potentially new and different lawmakers sitting on the committees that draft the bill and new lawmakers in leadership positions to drive the process. While the farm bill is intended to represent the needs and issues of farmers and communities and families nationwide, the representatives and senators who sit on the House and Senate agriculture committees, who themselves only represent a slice of the country’s landscape and electorate, get to do the lion’s share of shaping that bill.”

If you’re not sure whether to vote yes or no for a particular bill, Hackney has advice: “If there’s a bill that focuses on an issue you care about, you can look up its authors and cosponsors—these are the lawmakers willing to go on the record with their support for a bill.” Keep an eye out for the names of politicians who are familiar to you and try to determine if their values align with yours, then use their judgment to guide your own.

“For example, at NSAC, we’ve been organizing for several years around the Agriculture Resilience Act. It’s a bill that would address climate change by reshaping much of the US Department of Agriculture’s programming toward climate change action,” says Hackney. “It would increase resources and support for practices on farms that build diversity of crops and livestock, integrate perennial crops, keep the soil covered and integrate livestock into the landscape—all highly effective climate and agriculture solutions that can reduce emissions and build resiliency. Lawmakers who’ve endorsed this bill are essentially telling us: I support tackling the climate crisis by finding solutions through sustainable agriculture and food systems. You can find a bill’s cosponsors by using free, publicly available websites like congress.gov or govtrack.us.”

Diversify your approach

“If we could fix our food and farm system by simply voting with our forks or making one quick call to Congress or growing our own food, we’d be there already,” says Hackney. “The truth is it takes action on multiple fronts—especially if we want to get to the root causes of the problems in our food and farm system. That means both doing what we can with our individual food choices—within our means and our communities—to support food and farm businesses operating on values of sustainability and equity and choosing to engage politically to improve food and farm policy.”

The post How to Be a Food Policy Advocate in Your Community appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Opinion: Farmers Are Dropping Out Because They Can’t Access Land. Here’s How the Next Farm Bill Could Stop the Bleeding. appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The farm bill is a critical bipartisan package of legislation that renews every five years, and it expired on September 30, 2023. To avert a government shutdown, the Senate passed an extension bill to keep the essential programs running through the end of September 2024. This tightrope omnibus bill funds the SNAP program, farmer subsidies and USDA loan programs and grants. Eaters and farmers alike depend on this bill to get food on the table.

As a farmer’s daughter and farm advocate, I know that the farm bill has one of the greatest impacts on what you eat, how that food was grown and the ability of beginning farmers to find land in the first place. Many of my friends are farmers and I’ve seen them struggle against countless barriers, especially when it comes to accessing or purchasing land. In a recent National Young Farmers Coalition survey, 59 percent of young farmers named finding affordable land to buy as “very or extremely challenging.”

I’ve come to understand that despite where a farmer lives or what they grow, the lack of affordable land to farm is the number one reason farmers are leaving agriculture, the top challenge for current farmers and the primary barrier preventing aspiring farmers from getting started. The next farm bill can fix this.

Oregon agriculture is a part of my identity. I grow small-scale herbs, seeds and nursery starts in my backyard garden and work in the nonprofit agriculture world. My Land Advocacy Fellowship with the National Young Farmer Coalition empowered me to share my experience of growing up on the family farm with my senators and representatives offices on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.

Photo courtesy of Carly Boyer.

In June 2023, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced the awardees of the $300-million Increasing Land, Capital, and Market Access Program, which included 50 community-based projects for underserved farmers, ranchers and forest landowners. Three projects were funded here in Oregon, led by the Black Oregon Land Trust, Indian Land Tenure Foundation program and Community Development Corporation of Oregon. This program resulted in federal dollars going out the door, directly benefiting community-led land access solutions. It was also a one-time funding opportunity that I believe should be made permanent.

Following the creation of that one-time program, the bipartisan Increasing Land Access, Securities, and Opportunities Act (LASO) was introduced in both the House and the Senate. The LASO Act would expand on the promise of the Increasing Land, Capital, and Market Access Program. If enacted, this bill would authorize $100 million in annual funding for community-led land access solutions through the next farm bill. This would be a significant victory for young farmers, ranchers and everyone who has been fighting to win federal funding to address issues of equitable land access.

Flying to Washington, D.C with farmer Michelle Week of Good Rain Farm really impacted me. Hearing her experience of feeding more than 150 families in her Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) subscription yet still unable to afford to purchase farmland as an Indigenous woman in the Portland Metro area is alarming.

Across the country, farmland is being lost to development at a rate of more than 2,000 acres per day. Over the next 20 years, nearly half of US farmland is expected to change hands. Additionally, Black farmers across the United States have lost 90 percent of their historic farmland due to systemic racism and discriminatory lending. Today, according to the most recently available statistics, 95 percent of farmers are white in the United States and 96 percent of land owners are white. For these reasons and more, I advocate for federal reparations in the form of land access through the LASO bill.

We all eat and, in order to eat, we all need farmers. I hope you’ll consider getting in contact with your members of Congress today and urge them to support farmers by asking them to include the Increasing Land Access, Security, and Opportunities Act (H.R.3955, S.2340) in the next farm bill. With the current farm bill temporarily extended, it’s a pivotal moment to uplift critical policy changes like the LASO Act and invest in the health and well-being of our communities, our food system and the future we all deserve.

Carly Boyer (she/they) is a fourth-generation land manager, stewarding 140 acres in Polk County, OR. She works for Oregon Climate and Agriculture Network, an agricultural non-profit focused on Soil health. She is a board member for Rogue Farm Corps, a beginning farmer program and a Land Advocacy Fellow with the National Young Farmers Coalition advocating for the One Million Acres for the Future Farm Bill campaign in Washington, D.C.

The post Opinion: Farmers Are Dropping Out Because They Can’t Access Land. Here’s How the Next Farm Bill Could Stop the Bleeding. appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Opinion: Why the Farm Bill Isn’t Prioritizing the Right Things appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>But a closer look at our food system reveals many challenges. Its foundation relies on resource-intensive commodity crop production, which needs the majority of fertile lands to feed animals kept in confined spaces. It is heavily dependent on government subsidies, with large-scale farms scooping up more than 90 percent of subsidies, despite making up only three percent of the farms in the country. Our food system depends on cheap labor that consists predominantly of migrant workers, of which half are estimated to be undocumented. The societal cost, meaning the hidden costs associated with poor labor conditions such as child labor or unlivable wages, of our food supply chains is estimated at around $100 billion.

More than 70 percent of North America’s biodiversity-rich prairies have been replaced with wheat, soy, corn, alfalfa and canola, primarily used as livestock feed and biofuel. These crops are also the largest consumer of increasingly scarce river water in the Western United States. Agricultural run-off, including soil erosion, nutrient loss from fertilizers and animal manure, bacteria from animal manure and pesticides are the largest stressors to water quality of America’s streams and rivers. It’s estimated that the unaccounted cost of the food system on the environment and biodiversity is nearly $900 billion per year.

The efforts to truly create sustainable food systems do not go far enough. While they may be well intentioned, government grants and corporate projects aimed at “regenerative” and “climate-smart” agriculture are just tweaks to the system, not reforms to the status quo. Right now, the government needs to agree on priorities for the new Farm Bill. The current bill will expire in September, and we need new legislation that can address the real structural and societal issues in our food supply.

We need a radical change in the design of our food system. Following are five steps that can get us there:

Prioritize food for people instead of animals and fuel

One out of three calories in the US is wasted. We need to reduce food loss and waste, and repurpose it to feed people. Whatever food waste is left can then be repurposed to feed animals. Fertile agricultural soils should be used to grow diverse, nutritious crops for humans. Leave livestock and bison to graze marginal soils and native grasslands and upcycle food waste and byproducts into animal feed. This reorientation can produce around 10 to 20 grams of protein per person per day, or almost half of the recommended daily need. The farm animals that remain should be treated with respect and be given the best life possible.

Prioritize ecological efficiency, not economic efficiency

The ecological boundaries of natural resources, including soils, should dictate what’s grown, as well as where and how. Considerations such as organic matter and nutritional needs of the soil, local water availability, weather patterns, climate and local biodiversity should direct a farmer’s decisions around what to plant. We need to choose plants that support soil health and local biodiversity and are adaptable to the changing context of climate change—while also being nutritious for people. This will allow us to reduce our dependence on chemical inputs significantly.

Currently, the Farm Bill works to maximize income from commodity crops and livestock production, with the goal of maximizing economic efficiency. This has led to crop insurance programs and a host of other safety nets, which aim to protect producers from market instability and variations in yields and production. The majority of the financial incentives are for feed and biofuel crops; these programs do not incentivize farmers to prioritize native plants or ecologically beneficial crops or nutritious crops to nourish people, as they can get paid even if crops fail. The Farm Bill needs to take an ecological approach to subsidies and incentives, rather than squeezing economic returns out of a system without considering the long-term impacts.

Foster local and regionally diverse food networks

Give farmers access to markets, processing infrastructure, knowledge and grants, whether they be small, young, ethnically diverse or new. Market structures and business models should support fair income and wages for farmers and workers. Existing farmers need support in the transition to a balanced and ethical food system. The Farm Bill should prioritize these farmers when developing grants and subsidies to both attract and retain a diverse workforce.

Support healthy food for all people

Food needs to be healthy, nutritious and support dietary guidelines. It should prevent disease, not cause it. Food companies and retail need to offer and incentivize the purchase of healthy, sustainably grown foods. More than 70 percent of packaged foods marketed by leading food companies in the US include unhealthy levels of sugars, fats and salts. Government should shift focus from livestock feed and help producers transition to healthier offerings for human consumers. The Farm Bill is an opportunity to incentivize producers to move towards better, more sustainable offerings.

There is also an opportunity to expand SNAP and other food assistance programs within the Farm Bill. Programs within SNAP, like the Thrifty Food Plan, help people eat nutritionally balanced meals on a budget. Ensuring these programs are adequately funded and adjusted appropriately around times of inflation would go a long way to helping millions of Americans eat healthier.

Ensure resources to future-proof food systems

Re-routing the food system requires significant investments. Governments, banks, universities, food companies, NGOs and think tanks need to shift their focus from improving the economic efficiency of the animal-dominated farm system towards improving systems that embrace a nature-positive production of diverse nutritious foods for people. Funding should be allocated to research, grants, and private- and public-sector initiatives that help to rethink our current system. Rather than offering up small tweaks and changes, such as reducing enteric methane emissions from large herds or precision supply of chemical fertilizer to a corn plant, why not allocate that money to regeneratively grow food that nurtures our soils and people?

A Farm Bill fit for the future

We need a sense of urgency from everyone involved to make this happen. It will take funding, which can be reallocated within the Farm Bill to support this shift. Saying it’s too expensive cannot be an argument for inaction if it means we keep producing outside the ecological carrying capacity of our planet and sacrifice the futures of generations to come. Securing a long-term Farm Bill in 2024 that centers around these five steps is our opportunity to reform the system sustainably.

Sandra Vijn leads Kipster’s recent egg farm start in the United States. For more than two decades, she worked to advance corporate sustainability and sustainable food systems at the Global Reporting Initiative, Dubai Chamber of Commerce’s Centre for Responsible Business, Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy and WWF.

The post Opinion: Why the Farm Bill Isn’t Prioritizing the Right Things appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post How Will New Work Requirements for SNAP Benefits Affect Food Insecurity, Employment? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

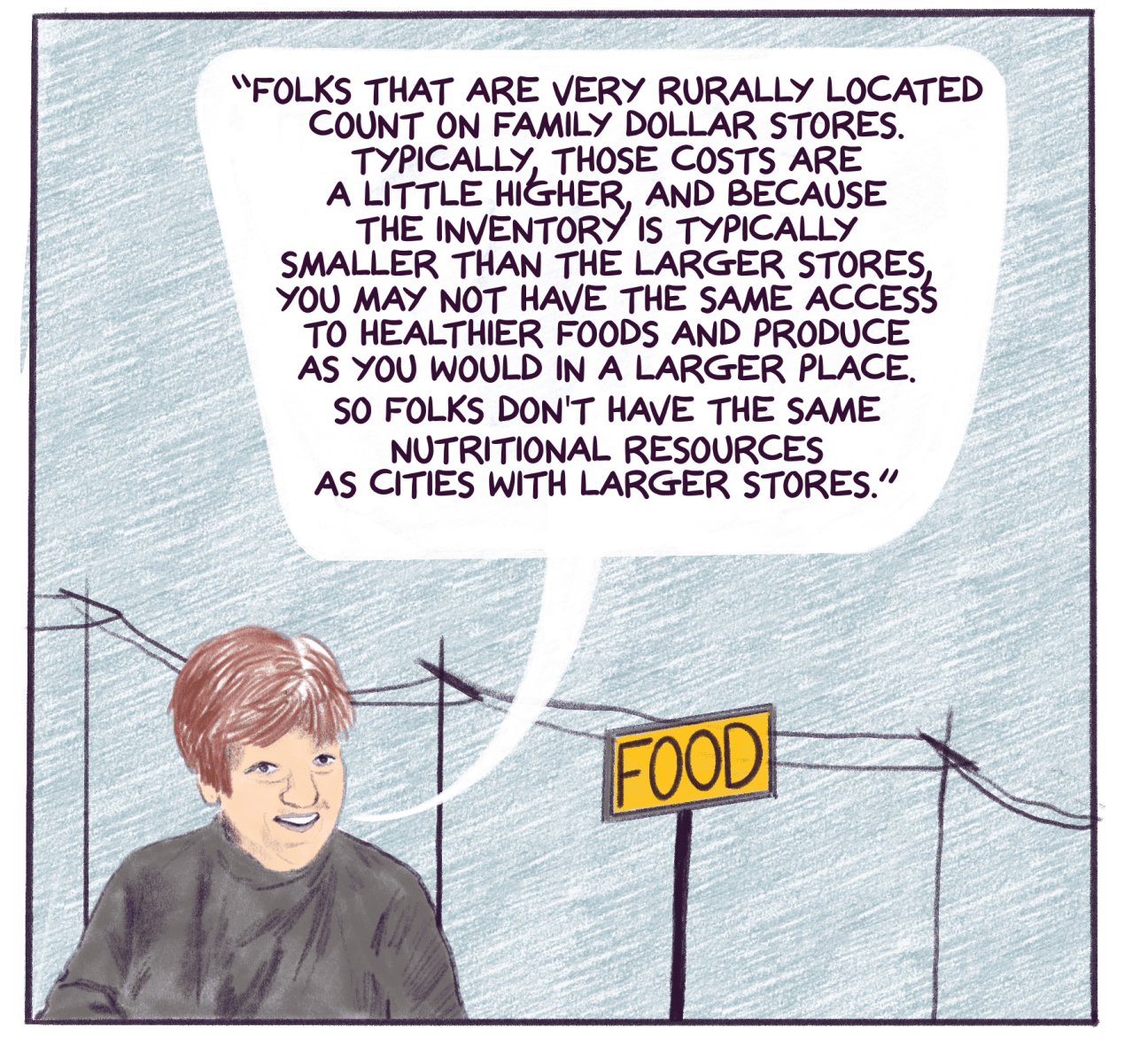

]]>Graphic Journalist Nhatt Nichols takes us to West Virginia, where comparable changes to the SNAP program were made back in 2018, to explore the outlook for people facing food insecurity and the communities they call home.

![Comic panel shows a speech bubble with a quote from the report that reads: “Our best data does not indicate that the program has had a significant impact on employment figures for the (ABAWD) population in the nine counties [that were part of the study] ... Health and Human Resources made approximately 13,984 referrals to SNAP in 2016, and of those only 259 gained employment.”](https://dailyyonder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/DY_SNAPWV1_panel17-1296x991.png)

![Comic panel shows Cynthia Kirkhart with quote that reads: “This year is the first year that Congresswoman [Carol] Miller's office and Senator [Joe] Manchin's office reached out to me with immediacy about our thoughts about the Farm Bill. Usually, we're the ones knocking on the doors first, you know, emailing and calling. And they were very responsive, to be the first one to do that outreach.”](https://dailyyonder.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/DY_SNAPWV1_panel34-1235x1296.png)

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

The post How Will New Work Requirements for SNAP Benefits Affect Food Insecurity, Employment? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Farmworker-Led Groups Push For Next Farm Bill to Include Worker Rights and Protections appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>“They see us as workers that they can exploit, pay a lesser wage to, that they can replace with machines. But we are the people in the first line of this food chain, and we have to be recognized and respected as such,” says Jiménez.

In 2016, Jiménez started Alianza Agricola, an undocumented farmworker-led advocacy organization fighting for farmworker rights in western New York. In 2019, the group helped in the fight to pass the Farm Laborers Fair Labor Practices Act (FLFLPA), a law that grants various labor rights such as collective bargaining, day of rest and overtime pay to farmworkers in the state of New York. It was a huge win, but it’s just the beginning of what’s needed.

Jiménez is not alone in his experience. An estimated 21.5 million people work to grow, harvest, process, pack, transport and sell the food that feeds Americans. Many of them put their well-being at risk to do so. Although undocumented workers face an extra set of challenges, millions of food and farmworkers, regardless of immigration status, are exposed to unsafe working conditions and paid low wages.

According to the Institute of Health, farmworkers are 35 times more likely to die of heat exposure. They are at risk for injury and illness from heavy machinery or pesticide exposure and in recent years have been disproportionately exposed to wildfire smoke and COVID-19. The vast majority of food and farmworkers are paid low wages, are ineligible for paid sick leave and are not entitled to overtime pay. Advocates say this year’s Farm Bill, a package of legislation passed every five years, presents an opportunity for some of these conditions to change, or at least improve.

The Farm Bill covers programs ranging from crop insurance to conservation incentives to nutrition assistance and more. It is incredibly influential, yet since its inception in 1933, the Farm Bill has failed to include protections for food and farmworkers. Labor rights are technically outside of the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) jurisdiction and covered by the Department of Labor, but their exclusion still reflects how our food system treats its workers, explains Sophie Ackoff, the Farm Bill campaign director at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS).

“Our tax dollars, our programs, are focused on the success of farmers and agribusinesses. And those 21.5 million workers who are doing the bulk of not only the work but the danger of producing food for our country are not in any way protected by the USDA,” says Ackoff.

Jose Oliva, the campaigns director at the HEAL Food Alliance, says the exclusion of workers from the Farm Bill isn’t accidental but rather the result of an exploitative history of agricultural workers—the majority of whom were African American—when the first Farm Bill was written. The bill was written to support farm owners, not workers. Over time, this has turned into support for large agribusinesses, Oliva explains.

“It is essentially a way for the government to ensure that the average farmer is not the recipient of most of the benefits that are built into the farm bill,” he says.

UCS, HEAL Food Alliance and Alianza Agricola, along with other farmworker-led groups, have been advocating for various bills to be included in the upcoming Farm Bill, which was supposed to be renewed in September 2023 but was recently extended to the end of 2024.

Protecting America’s Meatpacking Worker Act

Data from the Occupational Health and Safety Administration has revealed that the meatpacking industry is one of the most dangerous jobs in the food system, recording a disproportionately high number of severe employee injuries. Oliva describes working conditions in the meatpacking industry as horrendous. “These are places where folks are and during the pandemic were forced to work even while everyone else was able to work from home or not work at all,” he says.

Nearly eight percent of all early COVID-19 cases and four percent of early COVID-19 deaths were connected to meatpacking plants. At the same time, the profit margins of the meatpacking industry have grown 300 percent since the start of the pandemic. This bill, introduced by Sen. Cory Booker and Rep. Ro Khanna, would ensure safer line-processing speeds and stricter standards to protect meat and poultry workers from injury.

Supporting our Farm and Food System Workforce and The Voice for Farm Workers Act

Introduced by Sen. Alex Padilla, the Supporting our Farm and Food System Workforce and the Voice for Farm Workers Act would give food and farmworkers a dedicated voice within the USDA and strengthen their role and collaboration in decision-making processes. Despite being essential workers, Jiménez says agricultural workers are rarely heard by those in power. He hopes that is starting to change.

“I think it’s time the government put their eyes on who we are and what we’re doing,” says Jiménez.

Protect America’s Children from Toxic Pesticides Act

The United States uses more than a billion pounds of pesticides annually, a third of which are currently banned in the European Union. Each year, pesticide exposure harms as many as 20,000 farmworkers, causing them to suffer more chemical-related injuries and illnesses than any other workforce nationwide. Extreme heat also makes pesticides evaporate faster, a major concern as temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, Ackoff explains. The Protect America’s Children from Toxic Pesticides Act would ban the use of more than 100 toxic pesticides proven to harm both farmworkers and the environment.

Agricultural Worker Justice Act

Agricultural workers are some of the lowest paid workers in the country. In 2020, they earned on average $14.62 per hour, but in many states, the average pay is less than that. For undocumented workers, who make up approximately 50 percent of the farm labor workforce, the pay is even more precarious.

The Agricultural Worker Justice Act, introduced by Sen. Peter Welsch and Rep. Greg Caesar, would ensure that the USDA only purchases food from companies that pay their employees a living wage and would give the federal government tools to regulate and enforce safer working conditions for food and farmworkers.

Across the country, 80 percent of voters support better protections for food and farmworkers. There is immense opportunity to better support the backbone of our $1.053-trillion industry food and agricultural sector, says Ackoff. This year’s Farm Bill is funding-neutral, meaning no additional funding will be added, which could be challenging for the programs mentioned to get adequate funding. But Ackoff is hopeful the one-year extension will give more time to advocate for these changes to be made. Looking beyond 2024, advocates and farmworkers alike continue to fight for long-term change in the food system and to pass bills such as the Fairness for Farm Workers Act, which would update the nation’s 85-year labor laws to ensure farmworkers are paid fairer wages and overtime pay.

“That would be the most transformative,” says Ackoff.

For Jiménez, the fight for fair working conditions and respect goes beyond himself. Despite the risk, he says he will not stop advocating for what farmworkers—especially undocumented workers—deserve. He wants a better future for his children, one where their worth isn’t undermined by their employer.

“I think that we’re invisible still. And more than anything, we want respect and recognition,” says Jimenez.

The post Farmworker-Led Groups Push For Next Farm Bill to Include Worker Rights and Protections appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Farm Bill Extension Passed, Funding in Place Until September 2024 appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The funding resolution received bipartisan support, passing the House in a 336-95 call and the Senate 87-11. It allows for some breathing room for lawmakers to write a new farm bill, although farm groups and advocates urge legislators not to take too long.

Rob Larew, president of the National Farmers Union, said in a statement that while the NFU is encouraged by the support for the extension, it will now “urge Congress to channel that success toward getting a new farm bill done in a timely fashion. Family farmers and ranchers must have clarity about the status of farm programs to make informed planting and business decisions heading into the next growing season,” and the current extension only provides that clarity in the short term.

President of the American Farm Bureau Federation, Zippy Duvall, echoes that statement, asking the House and Senate to “stay focused” on creating a new, modern Farm Bill. “The current bill was written before the pandemic [started], before inflation spiked and before global unrest sent shock waves through the food system. We need programs that reflect today’s realities,” says Duvall. “While an extension is necessary, they’re running out of time to write a new bill.”

The leaders of both House and Senate agricultural committees seem to understand those fears, issuing a joint statement reaffirming their commitment to a new piece of legislation. “As negotiations on funding the government progress, we were able to come together to avoid a lapse in funding for critical agricultural programs and provide certainty to producers. This extension is in no way a substitute for passing a five-year Farm Bill and we remain committed to working together to get it done next year.”

Discussions and negotiations on the new Farm Bill have been stymied by opposing views on issues such as crop subsidies and funding for support programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which makes up around 80 percent of the bill’s spending. Republicans have pushed for more work requirements and stricter limits on SNAP accessibility, while Democrats have opposed the ideas.

The funding extension also avoids some of the dangers of letting key funding lapse at the end of the year, including what’s known as the “dairy cliff.” In the 1940s, permanent laws were created to establish safety nets for certain commodities deemed essential, including milk. The government was directed to buy dairy at inflated prices to support farm production. That law gets suspended with each Farm Bill, and without a new Farm Bill, there are fears that prices for dairy could shoot up dramatically.

The post Farm Bill Extension Passed, Funding in Place Until September 2024 appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post ‘We’re Cut Off’: Rural Farmers Are Desperate For Broadband Internet appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>But things got complicated, and quickly. As schools went virtual, little Hudson had to start her kindergarten classes online. “It was impossible. She could not connect, even with the hotspot device, because we get terrible reception. Nothing worked,” Stroup recalls. By the third day of school, the girl was crying, worried that the rest of her classmates would learn to read while she was left behind.

Stroup closed the laptop. She packed a lunch, took her granddaughter by the hand and walked down to the nearby creek. Together, the pair went through sets of picture books, until Hudson was able to sound out the words by herself.

Unfortunately, most issues caused by Stroup’s slow internet connection are not so easily solved. Stroup and her husband farm about 200 acres near Bessemer City, NC. They raise beef cattle and plant wheat and soybeans. But they have been consistently stymied when it comes to internet access on their farm. The issue became even more apparent during COVID. With no reliable internet connection, the Stroups were stuck selling person to person, in a time when that sort of business was the most dangerous option. “It crippled us, especially then,” says Stroup.

Even now, the lack of internet keeps the farm lagging behind. Most new farming equipment relies on an internet connection for GPS or other services. Even if the machine itself is not connected, you need the internet to fix it. “If you buy something new, they no longer give you a printed manual. As far as fixes and repairs and whatnot, you have to be able to download [a manual] off the internet.” So, Stroup is stuck with vehicles and equipment from the 1970s. “We can’t modernize,” she says. “We’re cut off.”

The Stroup farm is a classic example of those impacted by the middle mile effect. In an urban area, if an internet service provider (ISP) lays a mile of cable for broadband internet, it will be able to connect hundreds, if not thousands, of customers because the area is densely populated. In a rural area, that same mile of cable might connect a single family, so ISPs aren’t financially incentivized to run cable in those regions. What ends up happening is a lot of high-volume areas, surrounded by dead zones.

In fact, Stroup says she was told by one ISP that it would not run cable connecting her farm with a new housing development being built at the edge of her property line unless the Stroups paid for it themselves at a cost of more than $15,000. Stroup was shocked. “Are you crazy?” she thought. “Why am I paying for it?”

She sent a letter to her senator, who responded in 2021. He said there could be funding available for her through the Infrastructure Bill but that the decision of how and when to allocate those funds was down to the local level. He encouraged her to contact her governor. Stroup did. The governor’s response was to send her a fundraising letter.

“You hear on the news that there’s new funding available and billions of dollars pumped in to specifically connect the middle mile,” says Stroup. “Where is that funding?”

Lisa Stroup and her granddaughter. Photography by Lisa Stroup.

Mapping broadband’s dead zones

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines broadband as having download speeds of at least 25 megabits per second (MBPS) and upload speeds of at least three MBPS. The commission is in charge of keeping track of who is connected, what their speeds are and what needs to be done to get more Americans connected. It collects data, which gets compiled into the National Broadband Map. But the numbers on how many people are without broadband are anything but concrete. Some government figures put it at one in five US households, which would be 24 million households without access. The FCC’s 2020 report estimated that there were only 21 million individuals without access. But research from BroadbandNow, an independent firm, puts that number closer to 42 million Americans.

The data is all over the place because the FCC’s mapping system is not verified. “They rely solely on information provided by ISPs,” says Sascha Meinrath, the Palmer Chair in telecommunications at Penn State University. “Every ISP is providing these hyperbolically rosy estimates of where they serve and the speeds that are available in those locations. And there’s no meaningful verification, much less any accountability.”

Meinrath says when you get down into the data, you find that the majority of people who aren’t connected to the internet are rural Americans and the poorest in the country. “Neither of those constituencies have a whole lot of wealth to squander,” he says. But that’s exactly what’s happening, as they often have to pay more for worse service. In the Cost of Connectivity report, researchers found that Americans pay more for internet services than most other countries in the global north, and the gap in service disproportionately affects people of color.

Photography by Shutterstock.

Meinrath says a big part of the problem is that our ISPs don’t interoperate, meaning they don’t use each other’s equipment or infrastructure. And we’ve been here before. Picture an old black and white movie. There’s often a big boss, and they’ve got many different phones all sitting on their desk, each using a different telephone system. However, in 1934, the Communications Act passed with the mandate of universal service: the idea that everyone has the right to access communications services. The phone companies were forced to work together, and folks were able to have a single telephone for all of their needs.

But now, says Meinrath, we’re right back where we started with ISPs. They don’t share infrastructure, which is why you’ll often see multiple cellular towers in the same area, because each provider uses their own. It’s expensive and goes against the proven success of a universal service mandate.

So, what could the Farm Bill do about this? There are a few areas that we could start with, and Meinrath says the first one won’t cost the government a dime. “The Farm Bill could include a mandate that says anytime a provider reports to a federal agency that they provide service at an address, they must provide that service within 30 days or get fined $10,000 a day until they do,” says Meinrath. In other words, force the ISPs to show verification that they are doing what they claim. “You would spend nothing, and all of your maps would get super accurate, super quickly.”

Beyond that, we could look to bring back the idea of common carriage. Up until 2005, we had common carriage in the US, just like the universal service with telephones. “If you had a telecommunications infrastructure, you had to carry the traffic of your competitors. For example, we all remember the dial-up modem days and all those CD-ROMs sent by AOL. The reason they could do that is because whoever your local phone provider was, they had to allow you to use their infrastructure,” says Meinrath. But the government got rid of common carriage in 2005, so ISPs started focusing on only the most profitable areas, leaving “nothing in other areas. And if you look, we have spent more on infrastructure than it would cost to provide universal service.”

In the face of evidence and data, why have we set up a system that overbuilds in urban areas and nearly ignores rural spots? “The honest answer is because we’re idiots,” Meinrath says facetiously. “The opportunity cost to the country is an order of magnitude greater than the cost of just funding the build… It doesn’t make sense to the populace, not just rural, but the entire populace. And the only reason why we’ve done that is we have allowed ISPs to really dictate our policy, even when it is a vast detriment to society.”

Emily Haxby on her farm. Photography courtesy of Emily Haxby.

Struggling to connect

Emily Haxby, a fifth-generation farmer in Gage County, NE, has been vocal about what the lack of internet means for her and her neighbors. Or at least, she’s tried.

“I was actually doing a Zoom call with the Farm Bureau, the state board, and we were talking about broadband and connecting people, and those 11,000 missing locations in our state. And I kept glitching out, because I didn’t have an internet hotspot.”

Haxby and her family farm corn and soybeans and raise cattle and goats. When folks outside of agriculture think about those tasks, they may not realize just how connected modern farmers need to be. But Haxby uses wifi-connected monitoring systems for her crops and animals, but needs to drive into town to upload her data. All of the pivots she irrigates with are monitored and connected to the internet. And without reliable broadband, things get pricey. “A lot of people are using cellular [data] because that’s all that’s available,” says Haxby.

While Haxby does have some internet service, the speeds are much slower than she needs. For instance, the camera that she keeps in the barn to watch over her animals isn’t the most reliable. “It’s very glitchy when I’m watching my critters. Have you ever seen a lagging goat walking around a barn? It’s really funny,” she says. On average, the speeds in Haxby’s area are about six MBPS to download and two MBPS to upload (far slower than the 25-three benchmark set by the FCC). Haxby says she’d like to install more cameras, especially in the calving season, but she can’t rely on them with her current connectivity.

So, she tried to do something about it. She ran for supervisor in Gage County, and was elected on a platform that focused on internet access. She headed the Gage County Rural Broadband Project, with the aim of getting fiber internet out to at least 40 percent of the region.

Now, after months of work, the project is moving forward with the ISP NextLink. Cables are going in the ground now and connecting more than 1,000 homes. “People are so excited to finally be connected with something more reliable. I get so many calls [asking] ‘when will it get to my place?’” says Haxby. The initial phase of the connection project will service about 40 percent of Gage County, but Haxby says that’s just not enough. Even with a goal of 99 percent of the state, that leaves out one percent of Nebraskans, or roughly 20,000 people.

Haxby hopes these figures will finally compel ISPs to build out in rural areas. “I think for a long time providers have gotten complacent. There hasn’t been a push to get fiber to rural areas. I know there’s a cost barrier to that, but as a nation, we’re starting to see this is important,” she says. She hopes the Farm Bill comes with stipulations on its funding. “I hope the Farm Bill includes, at bare minimum, a requirement that any funding of broadband should be a minimum of 100/100 for speeds. We need to do what we can to make sure that the money that is being expended isn’t immediately outdated as we progress into the future.”

Broadband getting installed in Gage County. Photography by Emily Haxby.

Many legislators are promoting broadband. Georgia Senator Raphael Warnock and South Dakota Senator John Thune presented the bipartisan Promoting Precision Agriculture Act this spring, aiming to develop a national taskforce to determine connectivity standards for farm equipment. “Setting interconnectivity standards will help more agriculture devices, from a soil monitor in the ground to a drone overhead, talk to one another and transmit data efficiently, so that farmers can always have the latest information available to make decisions to improve efficiency, improve crop yields and lower costs,” a representative from Warnock’s office told Modern Farmer.

Senator Warnock, among other legislators, has also been vocal in pressuring the FCC to release broadband funding through the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, and his representatives say he is working to include specific language relating to broadband internet and precision agriculture within the Farm Bill.

At the state level, many government agencies are instituting grant policies to try and effectively distribute federal funding for broadband. In Minnesota, officials from Governor Tim Walz’s office say their data shows that roughly 180,000 households in rural areas are without broadband. So, they are distributing $100 million over the next two years through two programs: the Border to Border Broadband Development Grant and the Low Density Grant. The goal is to have all Minnesota homes and businesses connected to high speed internet by 2026.

But that could be where the issues lie. It’s not that people aren’t invested in solving this problem. It’s that too many people in too many disparate agencies are working independently, says Emily Buckman, director of government affairs with the American Farm Bureau Federation. “We have been supportive of the ReConnect program, which has become the USDA premier broadband program over the last five years and the most funded,” says Buckman. “We also will be supportive of just streamlining the programs that are currently in place. There’s a rural broadband program over at USDA that’s pretty similar to ReConnect…There’s just so many programs out there that we would like to see as much streamlining as possible, so that it makes it easier for the providers to apply and get those networks deployed.”

Broadband has been a priority for the AFBF for years, says Buckman, but the conversation ramped up during COVID. It was then that the federation members recognized broadband access as a priority to push for within the Farm Bill. “Farmers and ranchers depend on broadband, just as they do highways, rails, waterways, to ship food and fuel across the country,” says Buckman. “We hear a lot about sustainability these days; our members are doing a lot more with less. And a lot of that is due to the technology advancements that have occurred over the last several decades. And many of those do require connection.”

Broadband getting installed in Gage County. Photography by Emily Haxby.

Disconnecting

Lisa Stroup in Gaston County is doubtful that she’ll ever see high-speed internet on her property. It’s doubly frustrating, as she watches the new housing development at the end of her property get fully wired. “The people who could make it happen don’t respond to you. Nobody is familiar with [the issue]. I’m like, OK, so what do I do with that? Who do you call?”

Stoup eventually called her county office and was told they had no more funding to allocate to additional broadband, a fact that Justin Amos, the county manager’s chief of staff, confirmed. The county was able to participate in a grant program last year for the first time, partnering with the ISP Spectrum Southeast to leverage funds through the GREAT grant. Through that program, it connected 178 new locations in the county to high-speed internet. Amos also notes that the locations were picked by Spectrum, not the county.

However, the funds for that grant are limited, and Amos says that while the county is looking at future funding opportunities, it does not have the funds right now. “We are happy to reach out to speak with Spectrum or another ISP partner to find out their broadband expansion plans. Unfortunately, for this resident and others in similar circumstances, the cost of providing high-speed broadband is expensive. For example, it can cost $50,000 per mile to expand broadband and that assumes perfect conditions,” says Amos. It’s not uncommon for some of that cost to fall to the residents in rural parts of North Carolina, he says, so Stroup isn’t alone in getting a sky-high quote from her ISP.

It’s difficult to calculate what the lack of internet has cost Stroup. As the cost of fertilizer and seed continues to rise, just running the farm at a basic capacity is difficult. She can’t justify paying more for cellular data or hotspots. And driving into town to find internet service “cuts into your productivity and how much you can actually produce…Even though it’s looked at as a minor inconvenience to us, it has a major impact on the food supply,” says Stroup. So, she’s essentially given up the fight.

Stroup says that, regardless of what legislation comes out or funding deployed in her area, she will be completely surprised if her farm is ever connected. “They’re not going to waste their money on us.”

The post ‘We’re Cut Off’: Rural Farmers Are Desperate For Broadband Internet appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post The Farm Bill Expired. What Happens Now? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The US Farm Bill is a package of legislation that gets passed approximately every five years, and it more or less shapes the landscape of American agriculture. There have been 18 iterations of this legislation. A lot of important items are rolled into it: crop subsidies, crop insurance, nutrition assistance, conservation programs and much more. The legislation affects farmers, of course, but also every person in the country who eats and buys food, whether you realize it or not. This means that when a farm bill is delayed long enough, everyone may feel the effects in some way.

For a more thorough explanation of what the farm bill is, see our breakdown here.

What was the September 30th deadline? Why didn’t Congress meet it?

Our last farm bill was passed in 2018, so we’re due for our five-year refresh. In preparation for creating a farm bill that will last until 2028, relevant committees in the House and the Senate both draft versions of the bill, then debate and rewrite until the bills pass in both chambers. Then the bills are combined and must be passed by both the House and Senate before being sent to the president. But there have been a few key issues this time around that have held up the process.

Republican-proposed cuts to SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) prompted House Agriculture Committee Ranking Member David Scott to say in a press release, “I urge my Republican colleagues to proceed with caution. If they want to pass a farm bill that supports America’s farmers and families, they need to keep their hands off SNAP.” Lack of consensus about how to handle the farmer “safety net,” which includes crop subsidies, as well as how to allocate funds within budget constraints have also been notable issues. To learn about other priorities from US groups for this farm bill, read our recap here.

Do farm bill-related programs stop now that the bill hasn’t been re-authorized?

It’s complicated. The stakes are higher for certain programs.

For programs with mandatory funding from the farm bill, operations cease after the funding expires. Programs that get their funding through government appropriations (how the federal government decides to spend money), such as SNAP and federal crop insurance, can continue on without a current farm bill. There are also some programs that get amended and changed with each farm bill that, without reauthorization, would revert back to the law that introduced the program. Unfortunately, many of those laws are extremely outdated and wouldn’t work effectively in the present day.

Here’s what can happen to some of these programs now that the farm bill has expired:

- Title I crop subsidy and dairy support programs will expire at the end of the year. After that, the law reverts back to how it was written in the 1940s. This means less support for dairy farmers. For the consumer, it means prices for food items such as milk could go up by a lot.

- Title II conservation programs have been extended as part of the Inflation Reduction Act through 2031. “Those programs will continue to run as normal,” said economist/senior policy analyst for the House Agricultural Committee Emily Pliscott in a webinar discussing what to expect from this year’s farm bill.

- The Federal Crop Insurance Act is amended through farm bills but has permanent authorization and funding separate from the farm bill and, therefore, will not expire with the farm bill.

- SNAP, in theory, will be unaffected by the farm bill expiring because it runs on appropriations.

There are many other programs that depend on the farm bill for funding or authorization, and those will cease until the bill is reauthorized. These include USDA programs supporting organic farmers, farm-to-food bank assistance and some agricultural research. Read about how some of these programs were affected when the farm bill was delayed in 2018.

Is the narrowly avoided government shutdown a factor?

Yes. Congress just barely passed a continuing resolution on Saturday in time to dodge a government shutdown. If this stopgap hadn’t passed, the shutdown would have had an immense impact on programs funded by appropriations, such as nutrition assistance.

Fortunately, this temporary extension gives Congress 45 extra days to sort out the 12 appropriations bills that keep the country going. That means the next few months should contain big developments for government spending as well as the farm bill.

Has the farm bill been delayed before?

Yes. “It typically does take more than one Congress in one year to get a farm bill done,” said Jonathan Coppess, director of the Gardner Agriculture Policy Program, in the webinar. “So, if in fact we get into extension territory or this drags out past 2023, we are not in an anomalous situation.”

According to Coppess, the longest process was for the farm bill that was passed in 2014. Discussions began in 2011, and it was supposed to be reauthorized in 2012.

“The 2018 farm bill is actually the only one in recent history that has been reauthorized within the year of the expiration,” said Coppess.

What happens now?

Congress has until December to get it together to avoid dairy price hikes in January. “It puts a lot of pressure on us to not reauthorize right now but by the end of the year and either finish a conferenced farm bill, which will be really tight at this point in time, or to do a short-term CR [continuing resolution],” said Pliscott.

Continuing to avoid a government shutdown will also be critical.

“These farm bills, they’re the biggest give and take in the ag community that we have to deal with,” said Regents Fellow, extension economist and professor at Texas A&M University Joe Outlaw in the webinar. “We’ve done this 90-plus years, and they’ve never been easy.”

The post The Farm Bill Expired. What Happens Now? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post States Want to Put More Local Food on School Lunch Trays. What Does That Mean, Exactly? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>“It’s really fun when schools buy those apples and the kids get to learn about it,” says Kate Wheeler, Farm to Fork specialist for the Utah State Board of Education.

Elliott apples end up in state school lunches thanks to farm-to-school programs, initiatives that have expanded in the last few decades as a way to support children’s nutrition and regional agriculture. And it’s not just in Utah. With schools back in session, many school districts will be putting food from local farms on kids’ lunch trays. Farm-to-school programs can manifest in many different ways, but one pathway that has been increasingly adopted in recent years is Local Food Purchasing Incentives (LFPIs).

LFPIs are state-led programs allowing schools or early care programs to receive financial reimbursement for buying food from local producers. Buying local can be cost-prohibitive, so these types of programs are on the rise after calls for institutional support through state policy. Between 2001 and 2019, eight states and Washington, D.C. established programs across the country. Since the onset of the pandemic, seven additional states have adopted LFPI programs. These initiatives aim to increase local food purchasing for school meals, while providing children with nutritious food, strengthening local economies and helping school districts overcome cost barriers to local food.

No two of these programs are identical. But a question they all have to answer is what does “local” food mean, anyway?

Bespoke programs for states

In New York, School Food Authorities (nonprofits in charge of cafeterias) that spend 30 percent of their lunch budget on in-state food get an extra $0.19 cents back for every reimbursable lunch. Maine’s Local Foods Fund reimburses school districts with a dollar for every $3 spent on select local food, with a $5,000 cap for the school year—$5,500 if schools participate in a local foods training. Maine’s program began in 2001, but it received bolstered funding in 2019 and has been expanding and adjusting since then.

Some farm-to-school programs include farm education for students. (Photo: Shutterstock)

“It’s a constant evolution,” Robin Kerber, implementation manager for Full Plates Full Potential, an organization addressing food insecurity for children in Maine, said in a recent webinar hosted by the National Farm to School Network and Michigan State University’s Center for Regional Food Systems. “Every year, we’re reassessing what’s working, what’s not working, because we want it to work for everybody.”

This growing tide of LFPIs includes overlaps with other farm-to-school initiatives. One program distributes USDA funds to states to buy local food for schools. Additionally, some states are embracing a universal school meal model, wherein all kids eat for free at school, regardless of family income. Some of these include incentives for local food purchasing. This fall, students in Minnesota are experiencing the results of a universal meal policy for the first time.

“If there’s anything I can share, it’s that each incentive program is uniquely designed and administered,” says Cassandra Bull, policy consultant and host of the webinar series.

What is “local” food?

In practice, “local” is hard to define. Utah, for example, considers local to be anything Utah-grown. Wheeler says this approach isn’t without nuance. For example, schools can be reimbursed for Utah-made sour cream and cheese, but in the processing plants, milk from across state lines gets blended together to make these products. Utah counts these products as local as long as the product is made with 50 percent Utah-sourced milk.

“The other piece that we’ve struggled with a little bit is, is local a value in and of itself?” says Wheeler. “Or do we want to be promoting specific types of values-based procurements where we’re looking at how the food is produced and how it’s grown and worker treatment and all of those other values that sometimes we associate with “local” but aren’t necessarily inherently part of just buying something that’s close to you.”

But while big western states can equate “local” with “in-state,” things get trickier in the smaller states. New Hampshire is currently in the process of trying to pass a bill to support an LFPI. But only seven percent of New Hampshire is agricultural land, and many of the farms that it does have are dedicated to growing trees or hay.

Three children having lunch. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Eight of New Hampshire’s 10 counties border other states or Canada, and Stacey Purslow, program coordinator for the New Hampshire Farm to School Program within the University of New Hampshire Sustainability Institute, says three of their school districts have students that live in one state and go to school in another. What this means is that the definition of “local” is going to be different than “from New Hampshire.”

“We don’t grow that much here, and we have cross-state school districts,” says Purslow. “So, we wanted to support New England agriculture as well.”

Conor Floyd, grant programs manager for Child Nutrition Programs in the Vermont Agency of Education, acknowledges that defining local food is not cut and dry.

“One really thorny issue for us in our process was, what counts as local?” says Floyd. Vermont uses a definition created by the state legislature. Beyond having a succinct definition, there’s also the matter of enforcement. “The question for me was, who’s checking to make sure that this is local or not?”

Tracking local purchases

In order to be compensated, schools need to keep track of local purchases. This can be tedious, but it can provide an accurate picture of local procurement in the state and show farmers what schools are buying.

In Utah, schools have a tracking spreadsheet to use throughout the year. If they don’t keep track along the way, it can result in confusion and difficulty when it comes time to submit, says Wheeler.

“Some of our folks who are buying local are also not submitting for reimbursement because they feel like it’s too much work,” says Wheeler.

Harvest New York, an organization that helps grow the farm and food economy in New York state, created a database to help School Food Authorities track down qualifying products and get the paperwork they need.

“We need to make sure that the products are actually from New York, but the paperwork can’t be so onerous that our school food authorities don’t want to participate in it,” says Cheryl Bilinksi, local food systems specialist and Farm to School lead at Harvest New York.

Cows in a field in Utah. (Photo: Shutterstock)

For Wheeler, the success stories keep her going. New this year, Utah have established cooperative contracts with seven ranchers across the state. Every school in the state can order and be reimbursed funds for local beef or bison.

“The ranchers are so excited, and the schools are so excited,” says Wheeler. “Just seeing something work makes you realize it can continue to work, and that’s definitely one of the things that keeps you going.”

The post States Want to Put More Local Food on School Lunch Trays. What Does That Mean, Exactly? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Lack of Affordable Child Care is Hurting Young Farm Families’ Ability to Grow Their Businesses appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>“It feels like we’re always split between keeping the kids safe on the farm, being a good parent, and the needs of the farm,” Kerissa Payne said.

The United States has a child care crisis, yet the issue remains largely invisible in the farm sector. For too long, the nation has ignored the fact that farm parents are working parents who must juggle child care while working what can be one of the most dangerous and stressful jobs in America.

But as Bob Dylan might say, “The times they are a-changin’.”

For the first time in history, the two largest farm organizations, the American Farm Bureau and the National Farmers Union, have included child care in their policy priorities for the 2023 federal farm bill, a massive spending bill that passes every five years. As rural researchers, our conversations with policymakers suggest that there may be bipartisan support to help increase access to affordable quality rural child care as lawmakers hear from families.

Over the past 10 years, we have interviewed and surveyed thousands of farmers across the country to understand how child care affects farm business economic viability, farm safety, farm families’ quality of life and the future of the nation’s food supply. What we found debunks the three most common myths that have kept child care in the shadows of farm policy debates and points to solutions that can support farm parents.

Myth #1: Child care is a not a problem in the farm sector

Despite hearing from countless parents about their challenges with child care, the issue has been largely invisible among farm business advisers, farm organizations, and federal and state agricultural agencies. When we were interviewing advisers and decision-makers about this topic early in the COVID-19 pandemic, common first reactions we heard were: “child care is not an issue for farmers,” “we have never thought to ask about it” and “does it affect the farm business?”

Nationally, three-quarters (77 percent) of farm families with children under 18 report difficulties securing child care because of lack of affordability, availability or quality. Almost half (48 percent) report that having access to affordable child care is important for maintaining and growing their farm business.

Our research has consistently found child care is an issue that affects all of agriculture regardless of farm size, production system or location.

Growing up on a farm can be fun and educational, even as parents worry about risks. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Access to child care is especially acute in rural areas, where even before COVID-19, 3 in 5 rural communities were categorized as child care deserts. The high cost of child care left the Paynes in a position familiar to many Americans – they make too much to qualify for child care support, but they don’t make enough to afford the type of quality child care they want.

The Paynes’ experience reflects what we consistently hear from farmers: Child care affects the trajectory of the farm business and the ability of a farm family to stay on the land.

Myth #2: Farmers don’t want or need help with child care because they have family help

Perhaps one of the biggest myths we have heard is that farm parents want to do it all on their own, and when they need help, they have family members who can watch the children.

This might work if relatives are nearby, but almost half of farmers we surveyed said their own parents were too busy to help with child care, had died or were in declining health.

Often, farm parents have had to move away from family and friends to find affordable land. These parents consistently said the lack of community made it harder to take care of their children.

Farmers have repeatedly said that it is a myth that they don’t want help taking care of children. The problem is that they cannot find or afford help.

Myth #3: Children can just come along when doing farm work

While wonderful places to grow up, farms can be dangerous, with large equipment, electric fencing, large animals, ponds and other potential hazards. Every day, 33 children are seriously injured in agricultural-related incidents, and every three days a child dies on a farm.

Farm parents we spoke with recounted stories of children who died after falling out of a tractor, drowned when they fell into a pond, or were maimed by a cow. Almost all farm parents—97 percent—have worried that their children could get hurt on the farm.

In our research, parents talked about constantly weighing the risks and benefits of having children on the farm. One farmer had hoped his young son would “be my little sidekick and do everything I did.” However, the reality was different. He admitted he “didn’t think about a baby not being able to be out in the sun all day,” and he was struggling to balance care work and farm work. The government has spent millions of dollars on farm stress programs, yet child care’s role in creating and exacerbating farm stress is rarely talked about.

The Paynes asked a question we heard from many other parents: “Why is farming the only occupation where you are expected to take your kids to work?”

Keeping children busy and safe can divert time from parents’ own farm work. (Photo: Shutterstock)

Farm safety programs have traditionally focused on education. However, our research shows that farm parents are highly aware of the risks. Instead of education, parents explain that they need resources to help with child care—86 percent said they sometimes bring children to the farm worksite because they lack other options.

Finding solutions to support child care

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to America’s child care problems, particularly for farm parents, who are juggling raising their own families while working to feed and clothe the nation.

In our research, farmers spoke about a wide range of solutions: free or affordable quality child care, before- and after-school programs, better parental leave policies for wage and self-employed workers, financial support for safe play areas on the farm, college debt relief, free college tuition and more affordable health insurance.

Seeing his farm community struggling with child care, Adam Alson, a corn and soybean farmer in Jasper County, Indiana, co-founded Appleseed Childhood Education, a nonprofit dedicated to creating care and education opportunities for children from birth through high school. It opened its first early learning center in 2023 with a mix of public and private support.

Alson sees investing in child care as a path to attracting and retaining young farmers and families, and a strategy for growing and retaining the rural workforce.

“Throughout our country’s history, we have valued the importance of our rural communities and have invested in them and in sectors where the market does not go,” he said. “In 2023, quality child care is one of those sectors.”

As one Ohio farmer put it: “If America wants farmers, farm families need help with child care.”![]()

Shoshanah Inwood is an Associate Professor of Rural Sociology at The Ohio State University and Florence Becot is an Associate Research Scientist in Rural Sociology, Adjunct Faculty – National Farm Medicine Center at The Ohio State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The post Lack of Affordable Child Care is Hurting Young Farm Families’ Ability to Grow Their Businesses appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>